Central banks are concerned that they may lose the race for digital currencies to a private digital currency like Bitcoin (BTC). But Bitcoin and CBDCs are very different, with the former being of fixed supply while the latter are backed by fiat currencies. A brief comparison of the two.

As digital assets grow in popularity, so do government and central banks fears for their control over banking, payment systems and ultimately monetary policy itself. We have seen recent news articles highlighting concerns over stablecoins – digital assets that are typically pegged to a fiat currency – in Europe and other western countries. This is prompting central banks around the world to step up a gear and begin competing with stablecoins before it is too late, while also considering greater regulation and control over the launch of new coins.

Governments grappling to remain competitive

It wasn’t long ago that some central banks had concluded that distributed ledger technology (DLT) was not at a mature enough stage for use in major central bank payment systems. Central banks around the world reawakened to the prospect of Central Bank Digital Currencies (“CBDCs”) in light of COVID19, which has pushed society to become increasingly cashless. The increasing popularity of Bitcoin may have also had a part to play as it becomes entrenched in electronic commerce, with central banks at risk of losing the intensifying digital currency race.

The allure of greater efficiency through using a digital currency that can help significantly reduce settlement times and reduce accountancy costs has meant central banks are now stepping up a gear. According to the BIS (Bank for International Settlements), more than 80% of central banks are actively researching CBDCs. From March 2016 onwards the Bank of Canada launched Project Jasper, the Monetary Authority of Singapore began project Ubin, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority launched project LionRock and the European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of Japan launched the joint initiative Project Stella, focussing on cross-border payments.

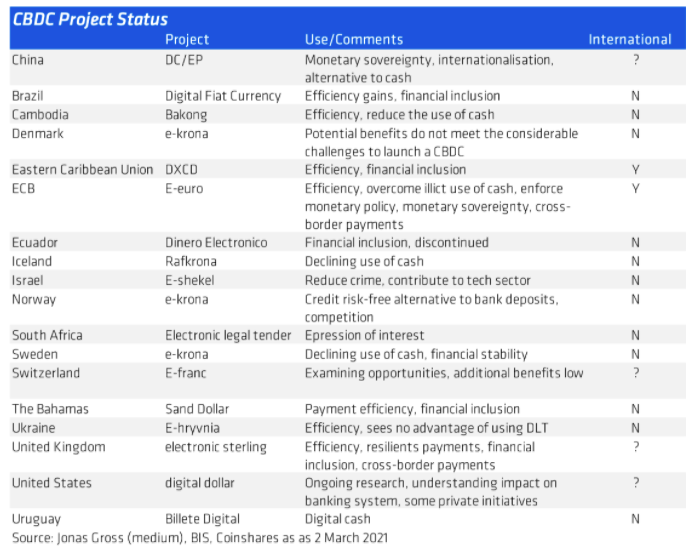

Around 40% have now progressed from conceptual research to experiments or proof of concept and around 10% have developed pilot projects, according to the BIS. China is likely to have the most advanced project for a major economy, known as the Digital Currency Electronic Payment (DC/EP), and is being piloted in four cities.

Implementation details still unclear

The ECB’s recent CBDC project concluded its digital euro public consultation this month but the details remain scant. It will decide to formally create a digital currency by mid-2021.There were a high number of responses to their consultation indicating great interest in the initiative, while the ECB President Lagarde said she expects there will be a digital euro. Interestingly, the ECB reiterated the four potential reasons for issuing a CBDC, namely demand for electronic payments, a decline in cash usage, potential dominance of a private digital currency such as Bitcoin, and European adoption of a CBDC issued by another central bank.

Some key considerations:

- CBDCs present an array of compelling merits, including the promise of near instantaneous payments and settlements, the eradication of black-market transactions, reductions in the costs of cash management and efficiency gains in accounting.

- They also present certain risks. Of these, privacy is perhaps the most pressing. CBDCs could potentially be programmed to control the spending of citizens, enforce negative yields on deposits and bail-ins, as well as to monitor income and spending in a way that is far more intrusive than we are accustomed to. Expect polarised political opinions on privacy and consequent delays.

- CBDCs in emerging countries are likely to grow popular as a method to attract foreign direct investment and also to monitor and control their population’s financial activity.

- While the momentum established in 2020 was significant, we should not expect fully functional CBDCs to emerge for some years – certainly not in the western world. There are a plethora of questions still to be answered, including whether central banks will adopt a direct ‘core ledger’ with the central bank or use an existing wallet provider utilising Distributed Ledger Technology, how KYC (know your customer) and AML (anti-money laundering) checks will be carried out, and how to manage the risk of hollowing-out systemically important commercial banks.

- CBDCs are likely to become very large and therefore a scalable wallet infrastructure will be required, this could become a big theme in 2021 as central banks look for credible wallet providers.

- Expect the regulation on existing and new stablecoins to intensify. The ECB recently stated that issuers should be subject to “rigorous liquidity requirements”, similar to those applied to money market funds, granting end-users a direct claim on the issuer or reserve assets. The European Commission recently proposed a Markets in Crypto-assets regulation would capture such stablecoins. The UK Treasury is currently consulting on its Regulatory Approach to Cryptoassets and Stablecoins.

The rise of stablecoins and the risk they pose to central bank hegemony could lead some to surmise that they are likely to be banned. It certainly has prevented the issuance of some, such as Facebook’s Diem (formerly Libra) project, but this must not be confused with potential controls/regulations of Bitcoin. We feel it is important to stress that CBDCs are not a candidate to replace Bitcoin.

The two are inherently different instruments, the latter being a peer-to-peer (as opposed to client-server), permissionless, censorship resistant distributed ledger, with a fixed and predetermined monetary policy, acting as an attractive non-sovereign store of value. CBDCs, on the other hand, look as though they will be designed to mirror the properties of their respective issuer’s fiat currency.

*Originally posted at CVJ.CH